Press

Onajide Shabaka in Biscayne Times

August 6, 2019

Biscayne Times

Elisa Turner

Onajide Shabaka enriches his art with the curious spirit of a documentary journalist and the observant eyes of a botanist. His travels as an artist from South Florida have taken him to places that include Mexico, South America, and the Caribbean. Almost wherever he goes, he is captivated by cultural histories and the uses of often overlooked plants.

In Miami’s Little Haiti, he says, a lot of vines growing on fences have medicinal properties. People might think they are ordinary weeds, but they aren’t. “There’s one that’s called serasee. It’s used for colds or to help drain your sinuses,” he explains. Amaranth is another such plant. It sometimes springs up in the cracks of sidewalks. “I’ve picked it in the Dominican Republic,” he adds, and used it to make his own Afro-Caribbean stew, callaloo. Both serasee and amaranth have African origins. Shabaka, whose great-grandfather was born a slave and lived in Fort Pierce, Florida, laughs quietly when asked to explain how he got interested in the attributes of weeds some urban dwellers would replace with manicured landscaping.

“I guess part of it has to do with having heard rumors in my family about people doing strange things, like somebody has some kind of medicinal plant to — quote, unquote — ward off the evil spirits,” he says. The rumors sparked his curiosity about such plants. He wondered if they might be edible. Then, he adds, “you just start investigating and find out some of these plants have African origins.”His desire to highlight his own African origins came about years ago. Onajide Shabaka is his legal name, but not his given name. He changed his name because, he says firmly, “I did not want to carry the name of a former slave master.” A family friend from Nigeria selected what Shabaka calls a “reincarnation name” for him. In the Yoruba language of West Africa, Onajide Shabaka means “the artist returns.”

This prolific artist, now 71 years old, has exhibited his art in dozens of venues throughout Florida, as well as in Los Angeles, New York City, Philadelphia, and Berlin. For the Little Haiti Cultural Complex in 2017, he filled a large planter with a small garden called “Antillean Lacunae: a litany of the botanical.” It grew amaranth, tamarind, and cassava. Currently he’s represented in an exhibit of artists’ books at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum FIU.

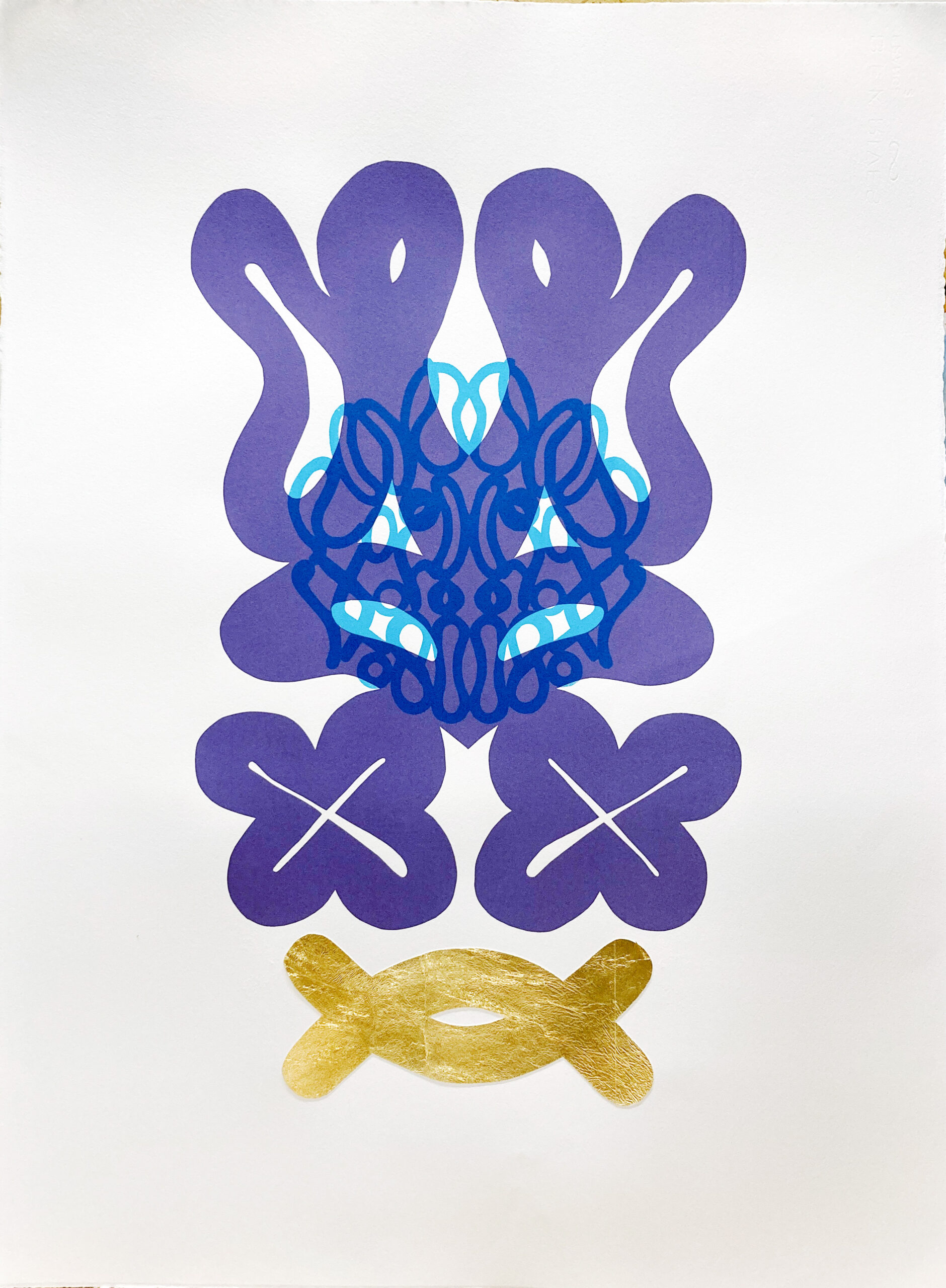

Shabaka’s curiosity about the African origins of plants coalesced in an exhibition that closed July 10 at Emerson Dorsch gallery. There was quite a range of art: documentary-style photographs, mixed-media works, and imposing installations. The exhibit was Alosúgbe: a journey across time. In the Saramaccan language of Suriname, the title means “as far away as the sun.” Saramaccan is spoken by the country’s Maroon population, descendants of African slaves who escaped from the Suriname plantations.

According to the Emerson Dorsch website, support for this exhibit came from various sources, including Locust Projects through its Wavemaker Grants, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs, and Diaspora Vibe Cultural Arts Incubator.

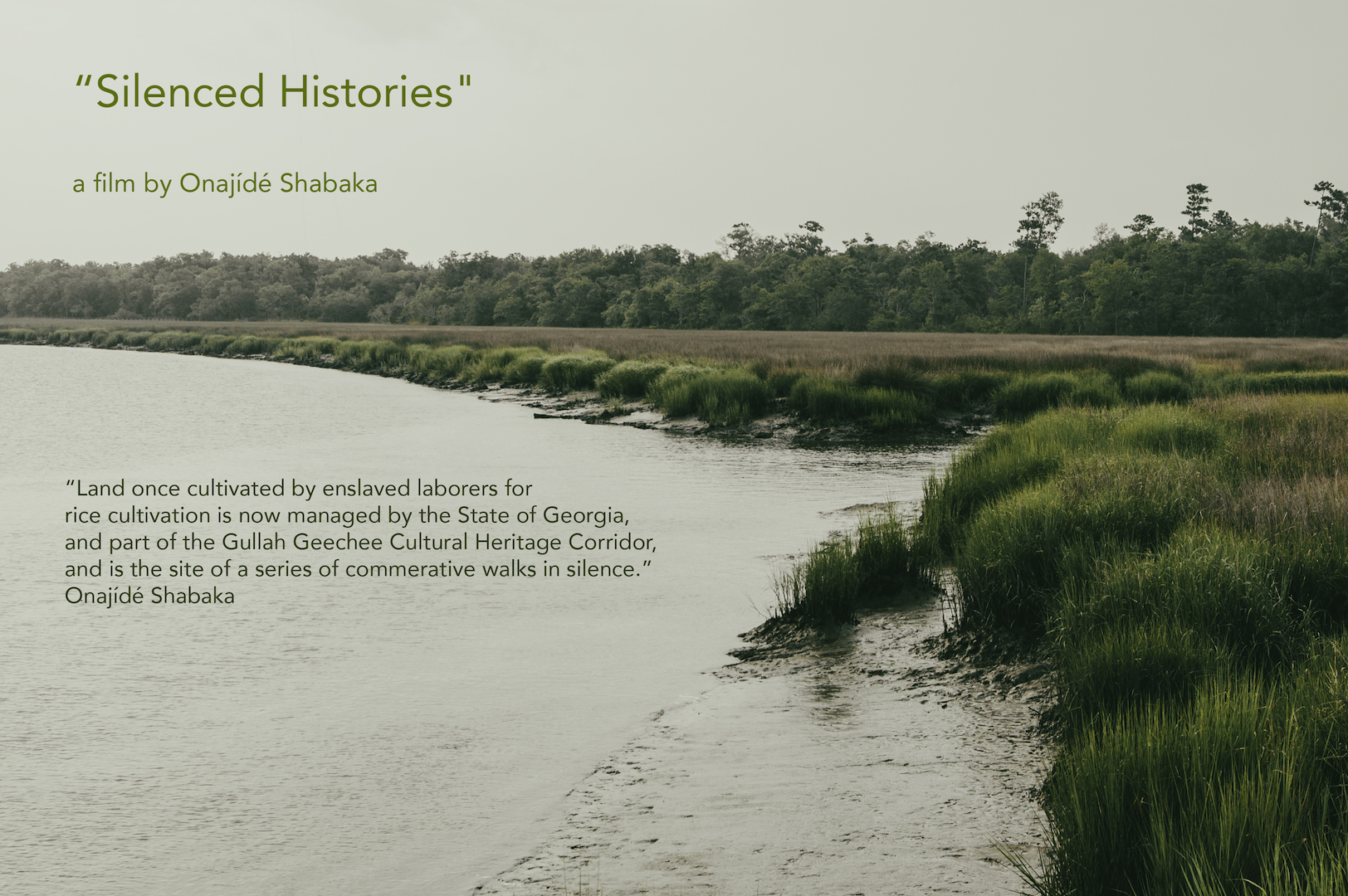

Shabaka’s Alosúgbe project, for which he plans to develop an artists’ book and film based on this gallery exhibit, earned him a 2018 Creator Award as part of Oolite Arts’ Ellies awards. The award came with an $8000 grant. “He was one of 38 grant recipients out of 516 applications. His idea really stood out,” says Oolite Arts president and CEO Dennis Scholl, praising the range of genres Shabaka envisioned: photographs, works on paper, artists’ book, and film. “He’s using plants metaphorically for the Atlantic colonial slave migration. That’s a wicked smart idea.”

Shabaka says much of the grant money he received went into developing art for the gallery exhibit, so he’s currently reapplying for funds to create the Alosúgbe artists’ book. The film will come later.

“We’re not there to fund the entire project,” says Scholl. “Our goal is to help the artist take it to the next level. I think any time you make a film, it’s hard, it’s expensive, and it takes time.”

Alosúgbe evolved in large part from Shabaka’s artist residencies in Suriname in 2016 and 2017. Although this former Dutch colony is located on the Atlantic coast of South America, wedged between French Guiana and Guyana, it is culturally Caribbean and a member of CARICOM (Caribbean Community). Shabaka’s Suriname residencies engendered research illuminating connections between that country’s agriculture, Southern U.S. states, Africa, and the Atlantic slave trade.

It’s a huge amount of geography and history to embrace in one body of work, Shabaka admits. He muses, “How do you bring all that together? I’m not trying to do world history.” His research yielded an answer at once stunningly simple and symbolically rich: rice. Shabaka learned that rice grown in Suriname has been shown to match the DNA of rice grown in Ivory Coast. That fact magnified an interest he’d had in Suriname since studying art in the early 1970s at the California College of the Arts in Oakland. “I remembered at the time I had done a little research for a sculptural project and saw wood carvings from Suriname and Ghana in West Africa that looked very similar,” he recalls.

For any artistic project, he says, he tries to “put his feet on the ground” of the place that’s his subject matter. Doing so “is important to make the history more alive,” he explains.

Traveling to Suriname was transformative. “Once I actually went there,” he recalls, “I felt the significance of being there and dealing with the Maroon population that had run away from slavery, had run away from plantations. In the history of plantations, that is significant because most slaves were not able to run away.”

Vivid photographs at Emerson Dorsch may have made visitors feel almost as if they, too, had put their feet on the ground in Suriname by walking in fields where Maroon women plant rice. His photographs also re-create the experience of traveling by river through the Amazon forest to those rice fields, visiting a historic site in the capital city Paramaribo, and happening across serpentine patterns made by nesting ant colonies.

Similar serpentine patterns reoccur throughout his art like calligraphy from a mysterious, persistent language. Other art is inspired by decades-old family correspondence in Fort Pierce.

Rice plays a persistent role in the shrine-like installation, Smuggled, saved, survived across continents. Surrounded by floor-to-ceiling swathes of translucent fabric are three bowls on a platform. Two are empty. “One is from South Carolina, where a lot of people were brought as slaves,” he explains. “The other is from Mali, where there’s still a vibrant rice culture.” The third contains rice from Suriname, not yet de-hulled by Maroon women working in the fields.